Short Film: Surprises and Contradictions in the Oral History of Sheldon Jackson School and College

Short Film: Surprises and Contradictions in the Oral History of Sheldon Jackson School and College

This exhibit was supported, in part, by a grant from the Alaska State Council on the Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts.

Thank you also to the Greater Sitka Arts Council and the Arti Gras music and arts festival.

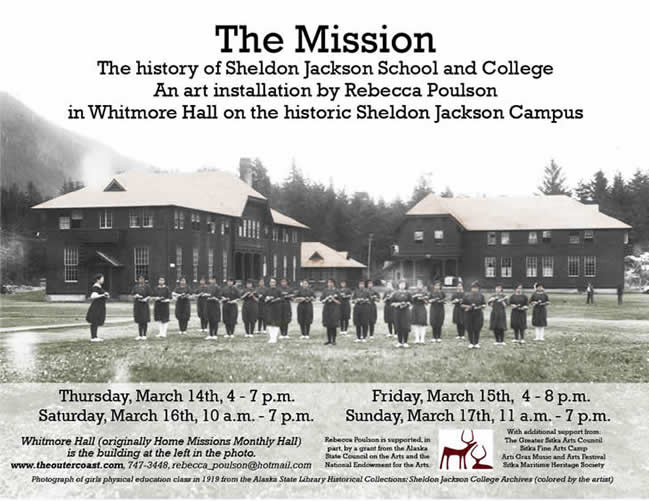

The Mission was an interactive art installation in Whitmore Hall on the historic Sheldon Jackson campus. Below is a description, comments, and acknowledgements, and photos:

Description

Over the weekend of March 14-17 (Thursday through Sunday) 2013, I presented The Mission, an installation of images and sound about the history of Sheldon Jackson School and College, in historic Whitmore Hall (1911) on the Sheldon Jackson Campus.

Most of the campus is now owned by the Sitka Fine Arts Camp. The school dates to 1878, and has been on this site since 1882.

In the west wing of the main floor was the early days of the school. On the walls I had historic photographs of students, staff, and the campus.

Throughout the building, there were five audio recordings, and two videos, all looping at about 3 ½ minutes.

In the west wing, in the south side of the hallway, the farthest room in the southwest corner was an encounter with Sheldon Jackson: facsimiles of letters from Sheldon Jackson to the president of Park College in Missouri, regarding M. Healy Wolfe.

Sheldon Jackson had taken Wolfe, then age five, from his home at Barrow to the Sitka school. From there, Jackson sent Wolfe to the Carlisle Indian School, and then to Park teachers college, from where Wolfe ran away. These letters are from Sheldon Jackson to the president of Park College about Wolfe, then a copy of the letter Wolfe sent to Sheldon Jackson, asking to be taken back.

Sheldon Jackson responded, in effect, that you've had your chance; now you must make your own way. What happened to this young man? I found a letter to editor Wolfe wrote, to the Tundra Times, in 1969 where he tells his story. This room also has photographs of the school, students, and Sheldon Jackson's museum from the early years.

In the next room, copies of pages of the Home Missions Monthly from 1915, featuring the Alaska missions, and pictures of students and teachers from about that time.

In the room closest to the main door, a six-minute excerpt from film shot by Les Yaw, superintendent of the school, between 1936 and 1940, and narrated by him in the 1980s. I projected this onto almost the entire wall. Two beds were made up, and an old suitcase we found in the attic lay on one. I called this room, "We Loved to Go to Presbytery."

On the north side of the hallway, the room in the far northwest corner had color photographs of the Presbyterian cemetery, along Indian River Road and in between the bike path and the campus and the recycling center. The graves here are nearly all of Sheldon Jackson students and families who died prematurely. A recording played of recollections of the losses of the 1930s at the Cottages, Kelly and Metlakatla Streets, which was once Mission property. In November 1937 four young men from this community drowned. The brief account of this tragic event from the school newspaper is also on the wall.

The other room on this side of the hall had the film from the 1930s and a photograph of the staff in 1932, with a recording of graduate remembering coming to school as a 7th grader in the 1940s.

Lobby and upstairs featured the years of the high school from the 1940s until the high school closed in 1967.

The lobby had historic photographs and copies of pages from yearbooks, from a reunion booklet, and photos of students from the high school, which ran until 1967. Upstairs was audio only, of four different former students. On one end of the hallway was more serious aspects – homesickness, kids punished for speaking their language, kids who didn't fit in. On the other end, was the more positive parts – basketball, choir, making friends with people from all over the state.

We'd also made up beds in several of the rooms, using bedspreads from the 1970s found in the attic, so that visitors could get some sense of what students saw.

The east wing, downstairs: The college, the end, and a beginning.

Images from yearbooks from 1968, 1976, 1985, 1990, and 1992, newspaper headlines, and school publications from the 1990s and 2000s, a chronology of the college years as recorded by Sheldon Jackson publications.

In the northeast corner I had headlines from the Daily Sitka Sentinel from the final crisis in 2007. I had audio playing of excerpts from an Assembly meeting in June of 2007, when they turned down a request for disbursement of $730,000 on a line of credit to the school to keep them afloat, which precipitated the closure of the school three days later.

In the southeast corner were excerpts from a KCAW interview with the school president in 2010, and newspaper headlines, when a potential deal with Dubuque University fell through in that year.

The last room - the former president's office - had a computer with a slide show of images of the current owner of the campus, the Sitka Fine Arts Camp. These beautiful images of volunteers doing carpentry, and Fine Arts Camp students making art, are a needed release and a ray of hope for the future.

Artist's Statement

I wanted to share some of what I’ve learned about Sheldon Jackson, mainly from interviews with elders, both students and staff. The photos and audio have been selected to highlight what I find most interesting and powerful about this place.

Back in 2011 my husband was cleaning out office desks in this building. The school had closed in 2007. There was still plywood over the windows, and the offices looked like the occupants had just left, with coffee cups and papers still on desks.

I had a sense of almost physical weight, in that space, of all that was lost – the children who lost family, language, culture; children who died at the school; and the recent loss by the staff and students at the abrupt closure, in disarray and debt, with the negative feelings from much of the Sitka community.

I don’t want to blame, condemn, or glorify. Every aspect of the school is complex and worthy of a good hard look.

Alice Zelhuber Smith and I have been interviewing people associated with the school since early 2012, and every interview has changed what I thought I knew about this place.

At the same time, I've been diving into the rich literature about Sitka and Tlingit people, especially the period of upheaval from the late 19th century on.

It was really great to be able to be in this building, as former students, former staff, and people from the community viewed pictures, told stories, and listened to the recordings. It was especially gratifying to hear people telling each other their insights or things they'd just learned, making their own connections from the audio, film and pictures. I intentionally did not interpret anything, just presented it as it was. The building itself, odd, large, and plain and worn, itself speaks to us.

As I was working to install this exhibit, some of what I put up was sad, and dark; most was happier. The darkest were the recording of an elder recalling the many deaths in the 1930s, and a recording of former students recalling the more negative aspects of the high school. I had looped the recordings onto cds. I had to borrow cd players. I had to try four different cd players before one would work to play the "death" recording; it took 2 before I could get the "negative" recording to play. All the other machines worked fine.

I really felt that this was the building asking me not to dwell on the hard, the dark things - asking to remember the bright, the youthful energy that was a much bigger part of the story. I felt like the building was wanting to be filled again with young voices, with children's feet pounding up and down the stairs.

My husband is not superstitious or religious or even spiritual. But when I mentioned to him that I felt like the building was alive, he said, "of course it is."

In fact, I think you can feel the human history of this place that goes back far beyond the school. The Tlingit Kiksadi Clan are the original owners; people have made their lives here for thousands of years. Some families at the Cottages, which was a mission settlement next to the National Park, are direct descendents of the Kiksadi defenders of Sitka, survivors of the Battle of 1804. A friend, the son of graduates, related to me a traditional story related to the rock that marks the campus boundary, and from where a nearby creek gets its name.

Missions are an aspect of colonization – Euro-Americans feeling entitled to resources, and considering indigenous people to be inferior. So missionaries work on the assumption that Natives would be better off taking on the ways of the dominant culture. This lack of respect, together with the taking of natural resources and land, has deep, far-ranging consequences. And, these attitudes are part of our thinking today.

Within this context of pervasive racial bias, some of the Presbyterian missionaries were good people, who genuinely wanted students to succeed. And, Native people are not passive victims. People a hundred years ago did not have a lot of options, but education here was a tool some used.

As we get into the years of the high school remembered by people alive today, it gets more complicated. Sheldon Jackson High School was a private school, and students paid tuition. Many were second- and even third-generation students. Unlike most Native boarding schools, all the students here wanted to be here (or, their parents wanted them here).

A reflection of the attitudes of the dominant culture was the 1956 Alaska Constitutional Convention. Neither the minutes, nor the document itself make any mention of Alaska's Native people, much less their aboriginal right to the land and resources. It was not intentionally left out – it simply did not occur to them, according to delegate Vic Fischer in his recent memoir.

One of the aspects of the school that is striking is the amount of loss experienced by students who came here in the 1940s, whether they grew up in the Cottages or in the Village, or from elsewhere in Alaska. I still need to get numbers, on just how bad it was – but so far everyone we've interviewed from this era lost parents, siblings or other relatives to accidents and disease.

Members of this generation as a rule are not big complainers, so you might never know about the trauma and loss of the generation who came of age in the 1940s and 50s, unless you are a nosy interviewer! They do not want to make a big deal of it, but I feel it’s important for us all to be aware of the trauma they experienced.

What first interested me in the school was its painful demise, and the slow twisting in the wind for years afterwards. Maybe people in Sitka were weary of supporting an institution that was unsustainable, and was not exactly good at communicating the actual state of affairs, or its mission. One of the staff members here at the end described the college as a wounded beast, who needed to die. But I’d grown up with the children of staff who devoted their lives to service through this school, and it seemed too bad that the failure and all the negative feelings would taint their work.

The main benefit the college gave was small classes, which, throughout the history of the school contributed to a family atmosphere. Unfortunately the small size meant the school could not hope to support itself.

Professor Molly Ahlgren once told me, “They can’t succeed. It’s not who they are.”

I hope that the exhibit, with only the images, historical documents, and words of people who made the school, tells much better than I can the deep contradictions and complexity of this place.

And finally, the Fine Arts Camp. I think that much of the success of this organization is because they have, and can express a clear mission: helping kids reach their potential through the arts. There is a long way to go before they can serve all the kids who could benefit (all kids), have strong Native involvement, and restore the physical campus; but they are on their way.

Things I learned, through the exhibit: I finally got to meet two sisters who came here in the 1950s, and finally got a sense of what a what we mean by School Spirit.

Acknowledgments

This installation was sponsored by the Greater Sitka Arts Council.

The Sitka Fine Arts Camp made it possible, with the use of the building, loan of equipment, and allowing me to disturb ghosts.

Eric Dow and Cora and Asa Dow did the backbreaking labor of cleaning up and arranging furniture, and are patient with me.

Thank you to Arti Gras, for including the show in their calendar.

All the actual cash that made this show possible comes from a grant from the Alaska State Council on the Arts and the National Endowment for the Arts.

Thank you to the Sentinel and to Nancy Yaw Davis, for access to old Sentinels and the Verstovian, and to Raven Radio for giving me a copy of Rob Woolsey’s interview with Dr. Dobler in 2010.

Thank you Cathy Poulson for cookies.

And, Alice Zelhuber Smith, whose determination to keep the story from being lost made the oral history project happen (see below).

Photographs:

Jim Simard, and the Alaska State Library Historical Collections, Sheldon Jackson College Archives.

Sue Thorson, Sitka National Historical Park, for Merrill images of students, and the picture of Sitka Champs 1947, from the Park’s Ellen Hope Hays photo collection.

James Poulson, for the photographs of the Presbyterian cemetery.

Other images came from Kathy Ruddy of Juneau.

Video:

Video excerpts are from Sheldon Jackson School 1935-40, a 27-minute video of film taken in those years and narrated in the 1980s by Les Yaw. This was mastered for dvd by his son Chuck Yaw and published by the Sitka Maritime Heritage Society. Copies are available for $10. Proceeds benefit the SMHS, with a dollar going to a republishing fund for Les Yaw’s books.

Audio:

The Assembly meeting of June 26, 2007 is from the archives of the City and Borough of Sitka.

Interview with David Dobler from 2010 is by Raven Radio.

Other interviews are part of an ongoing Oral History of Sheldon Jackson School and College, by Alice Zelhuber Smith and myself. These interviews will be archived at the University of Alaska Fairbanks Oral History Program, and eventually at the Stratton Building, now part of the Alaska State Museums. They are also broadcast, if the interviewee is willing, on local access television.

Support for this recording and archiving the interviews, and for making a written narrative and the short video, comes from the Alaska Humanities Forum.

Voices heard belong to: Charles Daniels, Herb Didrickson, Fred Hope, Rachel (Demmert) James, and Gil Truitt; all used with permission.

If you would be willing to be interviewed, please contact Alice or myself, at 747-3448, email rebecca_poulson@hotmail.com.

Below are a few photos of the installation:

Sheldon Jackson High School graduate Marie (Mork) Laws, and artist Rebecca Poulson. Photo by James Poulson, Daily Sitka Sentinel

Visitor Kristen Homer viewing images from the last high school yearbook, 1967. Photo by James Poulson, Daily Sitka Sentinel

Bill and Nancy Yaw Davis and artist Rebecca Poulson. Nancy Yaw Davis's father, Les Yaw, was superintendent of the Sheldon Jackson High School, and first President of the college. Photo by James Poulson, Daily Sitka Sentinel

Nancy Yaw Davis and Rebecca Poulson, identifying individuals in historical 1935 photo of Sheldon Jackson orchestra. Photo by James Poulson, Daily Sitka Sentinel

Visitors viewing images from yearbooks and college publications. Photo by James Poulson, Daily Sitka Sentinel

Visitors viewing images from yearbooks and college publications. Photo by James Poulson, Daily Sitka Sentinel

Visitors – the young man second from the left told a story about how his grandmother went to Sheldon Jackson High School, then ran away, intending to join the Canadian Army as a nurse during WWII. She was brought back by her uncle, and went to work at the Pius X School in Haines. Photo by James Poulson, Daily Sitka Sentinel

Installation view – film from the late 1930s, with narration by the first college president Les Yaw. Photo by James Poulson, Daily Sitka Sentinel

Visitors – Artist Peter Williams, center, is the grandson of long-time Sheldon Jackson College history professor Frank Roth. Photo by James Poulson, Daily Sitka Sentinel